The Illusion of Control: A Critical Analysis of the Copyright Office’s Position on AI Authorship

The U.S. Copyright Office’s January 2025 report on AI-generated works represents a pivotal moment in copyright law’s evolution – or perhaps more accurately, its resistance to evolution. The Office has staked out an unequivocal position: AI-generated works merit no copyright protection absent demonstrable human authorship. Their reasoning, while cloaked in traditional copyright doctrine, reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of both technological reality and creative practice.

At its core, the Office’s position rests on three increasingly unstable pillars: a rigid interpretation of constitutional human authorship requirements, a technically naive view of AI systems as uncontrollable “black boxes,” and a reductive characterization of prompts as mere instructions rather than creative expression. While each of these foundations might have seemed solid in the era of mechanical reproduction, they crumble when confronted with the realities of modern artificial intelligence.

The Paradox of Indistinguishability: A Fatal Flaw in the Copyright Office’s Position

Before delving into the intellectual foundations of the Copyright Office’s reasoning, we must confront its most glaring practical contradiction: in a world where artificial intelligence can produce works indistinguishable from human creation – even to the most discerning and erudite observer – how can we rationally maintain a legal framework that confers protection based solely on provenance? This fundamental paradox strikes at the very heart of the Office’s position, challenging not merely its practicality but its philosophical coherence.

When two works prove identical in every discernible aspect – their creativity, their sophistication, their cultural value – yet the law would protect one while leaving the other to the public domain based solely on its origin, we face not just a practical quandary but an intellectual crisis in copyright doctrine.

Enforcement Impossibility

Consider two identical novels – one written by a human, one generated by GPT-4 through careful prompting. The Copyright Office would grant copyright to the first but not the second. Yet if these works are literally identical, how could this distinction ever be meaningfully enforced? Courts would face an impossible task of verifying authorship when infringement claims arise.

Market Reality

The marketplace cannot function based on invisible distinctions. Publishers, galleries, streaming platforms, and other content distributors need clear, verifiable ways to determine what they can license and distribute. The Office’s position creates an unworkable scenario where identical works have radically different legal status based on factors that cannot be practically verified.

The Authentication Crisis

The Copyright Office’s position implicitly requires a provenance system that cannot exist. While they suggest authors should disclose AI usage, there’s no reliable way to verify such claims. We’re entering an era where:

– AI can generate human-like text

– Humans can imitate AI-like outputs

– Hybrid workflows blur the boundaries

– Creation processes are often undocumented

This makes the Office’s human authorship requirement increasingly detached from practical reality.

The Economic Contradiction

Copyright exists partly to provide economic incentives for creation. But if two identical works enter the market – one protected, one not – this creates bizarre economic distortions. Why should one creator enjoy monopoly rights while another, producing identical value for society, receives none?

The Scale Confusion

The Office’s concerns about AI flooding markets with content confuses technical capability with copyright principles. The ability to generate content quickly has no bearing on whether individual instances of generation involve human creativity.

The Limitations of Linear Thinking

The Copyright Office’s analysis, while methodical, reveals a concerning rigidity in its conception of creative expression. Their dismissal of prompting as merely “instructions that convey unprotectible ideas” betrays a fundamentally mechanical understanding of the creative process that seems more at home in the industrial age than our current technological renaissance.

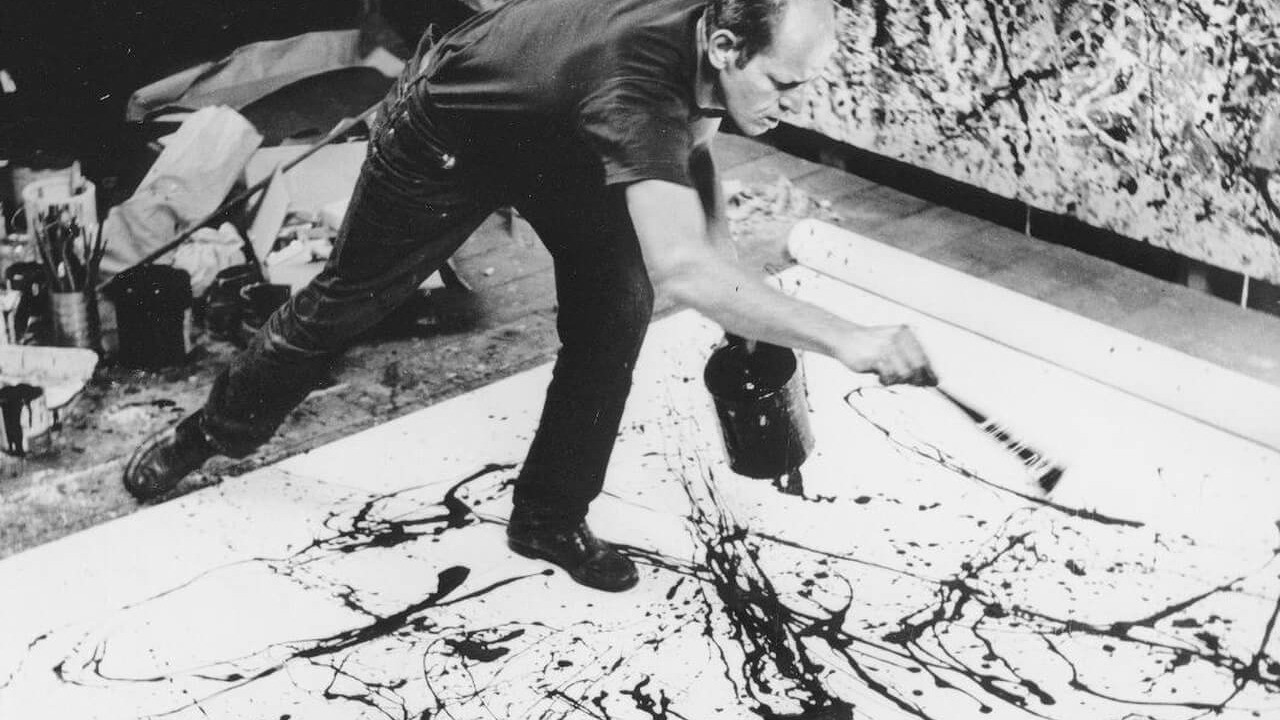

Consider their handling of the “black box” argument. The Office emphasizes AI’s unpredictability as evidence of insufficient human control, yet this reasoning would paradoxically disqualify many recognized forms of artistic expression. Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings involved significant unpredictability, as do crystalline glazes in ceramics, analog photography’s chemical processes, and generative music compositions. The Office attempts to distinguish these cases by arguing that traditional artists maintain “principal responsibility” for executing their vision, but this distinction becomes increasingly tenuous under scrutiny.

The Fallacy of Perfect Control

Perhaps most troubling is the Office’s implicit requirement for near-perfect control over expressive elements. This standard, if applied consistently, would invalidate numerous works currently protected by copyright. A photographer cannot control every aspect of natural lighting, just as a documentary filmmaker cannot dictate every moment captured. The essence of creativity often lies precisely in the dialogue between artistic intent and unpredictable elements.

The Office’s argument that iterative prompting amounts to merely “re-rolling the dice” reveals a particularly mechanical understanding of creative processes. This characterization ignores the sophisticated judgment exercised in recognizing and developing promising directions, refining approaches based on results, and making informed creative choices throughout the iterative process. It’s akin to arguing that a sculptor merely “re-rolls the dice” with each adjustment to their clay.

This ignores how prompt chains and feedback loops create a coherent creative process. When an artist adjusts their prompts based on previous outputs, they’re engaging in a form of creative dialogue with the system – not unlike a photographer taking multiple shots while adjusting composition and settings.

A Question of Agency

More fundamentally, the Office’s position reflects an outdated model of creative agency that insists on direct physical manipulation rather than recognizing the legitimacy of creative direction. This perspective would seemingly invalidate the creative contributions of film directors, choreographers, and other artists whose work primarily involves directing rather than executing.

The Human Element in Technological Creation

What’s particularly striking is how the Office’s analysis fails to engage with the uniquely human elements of prompt crafting. A well-crafted prompt often embodies deep understanding of artistic traditions, cultural references, and aesthetic principles. It requires the ability to translate abstract concepts into concrete descriptive language, to anticipate how different elements will interact, and to navigate the complex relationship between technical parameters and artistic outcomes.

The Office’s dismissal of these elements as mere “instructions” misses the forest for the trees. It’s like reducing a film director’s work to “instructions to point the camera” or a conductor’s art to “instructions to play notes.” This reductive analysis fails to recognize how creative vision can be meaningfully expressed through direction and curation.

Historical Evolution of Copyright in the Face of Technological Change

The irony of the Office’s position becomes clear when viewed through the lens of copyright history. In 1884, when the Supreme Court faced the question of photographic copyright in Burrow-Giles, critics argued that photographs were merely mechanical reproductions created by cameras, not human authors. The Court wisely saw through this technological determinism, recognizing that creative choices in composition, lighting, and arrangement constituted authorship – even though the final image was “generated” by a machine using chemical processes the photographer couldn’t directly control.

Today’s Copyright Office, confronting an analogous question about AI-generated works, has chosen a far more restrictive path. Their position that prompts cannot constitute authorship because they don’t provide “sufficient control” over expressive elements would, if applied retroactively, invalidate numerous forms of recognized artistic expression. Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, John Cage’s chance-based compositions, and even modern digital photography all involve significant elements of unpredictability and technological mediation.

The advent of computer-generated art in the 1960s prompted similar concerns. When artists like Michael Noll began creating algorithmic artwork, questions arose about authorship of computer-output. The Copyright Office’s own 1965 report acknowledged the need for nuanced analysis rather than categorical exclusions [1].

The Technical Reality of Modern AI Systems

The Copyright Office’s characterization of AI as a “black box” that merely generates random variations betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of how modern AI systems actually work. Contemporary large language models and image generators employ sophisticated attention mechanisms that create meaningful relationships between prompts and outputs.

Consider how DALL-E or Midjourney process prompts:

- Attention layers map semantic relationships between prompt elements

- Cross-attention mechanisms allow precise control over how different aspects of the prompt influence different parts of the output

- Parameter controls like seeds, negative prompts, and style weights enable fine-tuned guidance of the generation process

- Advanced techniques like regional prompting and iterative refinement provide granular creative control

The Office’s analysis fails to engage with how these technical capabilities enable creative expression through direction rather than direct manipulation. When an artist crafts a prompt like “cyberpunk cityscape with art nouveau elements, golden hour lighting, 85mm lens” they are making specific creative choices about:

– Artistic style fusion

– Atmospheric conditions

– Technical parameters

– Compositional elements

These choices meaningfully shape the output in ways that go far beyond mere “instructions.” The system’s interpretation of these elements through attention mechanisms creates a sophisticated dialogue between human creative intent and technological capability.

The False Dichotomy of Assistance

A particularly problematic aspect of the Office’s reasoning appears in their distinction between “assistive” and “generative” AI use. They argue that AI as a tool preserves copyright eligibility, while AI as a generator negates it. However, this binary classification breaks down under technical scrutiny.

Consider image inpainting – is an AI system that fills in missing parts of a photo being “assistive” or “generative”? The distinction becomes arbitrary. The same neural network architecture could be used in both scenarios, making the Office’s bright-line rule technically incoherent.

A More Sophisticated Framework

What’s needed is not a lowering of standards for creative control, but a more sophisticated framework for understanding how human creativity manifests in technological contexts. This framework should recognize that:

- Creative control exists on a spectrum rather than as a binary condition

- Artistic judgment can be exercised through direction and curation as well as direct manipulation

- The unpredictability of creative tools does not necessarily negate human authorship

- The relationship between artist and medium is often dialectical rather than purely deterministic

While the Copyright Office’s cautious approach has merit, it may be unnecessarily rigid in its treatment of prompt-based creativity. A more nuanced framework could better serve copyright’s fundamental purpose of promoting human creativity while adapting to new technological realities.

The key is maintaining meaningful standards for creative authorship while recognizing that human creativity can be expressed through new interfaces and processes. This requires carefully balancing tradition and innovation rather than categorical exclusions based on current technological limitations.

As AI tools evolve and creative practices adapt, copyright law must find ways to protect genuine human creativity in all its forms while maintaining appropriate standards for creative control and expression. This suggests the need for ongoing dialogue between creative communities, technology developers, and policy makers to develop frameworks that serve copyright’s fundamental purposes in a changing creative landscape.

The path forward lies not in rigid categorical distinctions but in carefully crafted standards that can identify and protect human creative expression regardless of the technological interface through which it is expressed. This approach would better serve both creative communities and copyright’s fundamental goals.

FOOTNOTE:

[1] Here is exact quote from 1965 Annual Report of the Copyright Office:

“It is not unreasonable to expect that the number of works proximately produced or “written” by computers will increase. In many cases the application may not reflect the true nature of the authorship, and registrations will be made that would not be if the actual facts had been known by the Examining Division. The problem is complicated by the fact that we cannot take the categorical position that registration will be denied merely because a computer may have been used in some manner in creating the work. After all, a typewriter is a machine that is used in the creation of a manuscript but this does not result in the manuscript being uncopyrightable. The crucial question is whether the work is one of human authorship with the computer merely being the instrument,”

Founder and Managing Partner of Skarbiec Law Firm, recognized by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna as one of the best tax advisory firms in Poland (2023, 2024). Legal advisor with 19 years of experience, serving Forbes-listed entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups. One of the most frequently quoted experts on commercial and tax law in the Polish media, regularly publishing in Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Author of the publication “AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto. Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator” and co-author of the award-winning book “Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy” (Security of a Modern Company). LinkedIn profile: 18 500 followers, 4 million views per year. Awards: 4-time winner of the European Medal, Golden Statuette of the Polish Business Leader, title of “International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.” He specializes in strategic legal consulting, tax planning, and crisis management for business.